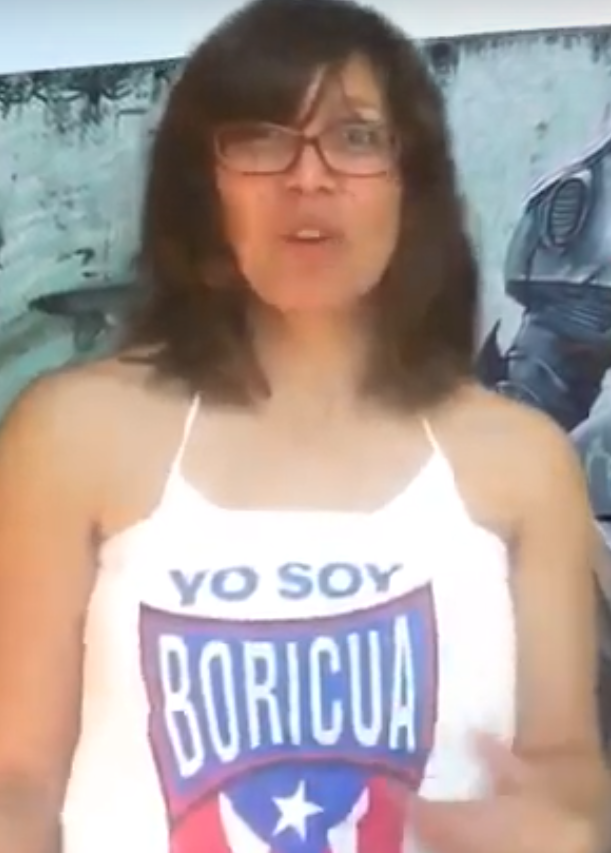

A recent study found Floridians of Puerto Rican descent experienced “secondary trauma” from the storm, but also a renewed sense of identity and purpose. In this article, “Super Gringa” writes about art as a way to reclaim lost identity.

I’m Puerto Rican. But I wasn’t born in Puerto Rico. My parents were. They migrated with their families to New York in the 1940s, along with hundreds of thousands other Puerto Ricans looking for better economic opportunities. They retired in Orlando, Florida in the 1980s.

“After 23 years in the NYPD,” says my dad, “I was able to retire, and I’d had enough of the cold.”

More than 30 years later, I have made a tradition of being here every winter, to escape the below zero temperatures of the Northeast. I know. How bougie of me. But I work remotely. So I can live wherever I want. And anyone who lives this digital nomad/virtual gypsy lifestyle uses Airbnb or Couchsurfing to find temporary homes, Uber and Wanderu for rides, Citibikes for sightseeing and Tinder for meeting people and conducting market research:

- “Oh. I didn’t realize you are Puerto Rican,” said Match #1, who I screened via phone before taking him on a bike ride through all my old neighborhoods. He is a white boy who had migrated to Orlando 15 years ago from Chicago and described certain neighborhoods as “bad,” one of which was Bithlo. Yeah, back in the day, I thought it was “bad,” too, but for different reasons. It was as red necky as it sounds. But I found it’s now pronounced “Beeethlo,” because it’s majority Puerto Rican…which I guess to him equals “bad.”

- “Eres Boricua? En Orlando hay tanto… pero son cafres (low class),” said Match #2, who called me through Whatsapp because he is a Colombian international student (yes, that’s me stereotyping his choice of communication platform). He has lived in Orlando for three years and was delightfully forcing me to speak my mocho Spanish, which led to the question I always get, “De donde eres?” At least he complimented me on my Spanish.

- “I think I’m the only Puerto Rican to win Jeopardy,” said Match #3. I was impressed by his Jeopardy smarts, so I called him a “Nerdirican,” which he then defined as, “Puerto Ricans who don’t beat their hoes.”

- “Oh hell…you’re Puerto Rican? I’m in trouble,” texted Match #4, who migrated to Orlando from Wisconsin two years ago.

When I string these comments together, they paint a tiny picture of Orlando’s place in the Ricanstruction story post Hurricane Maria, and the longer, historical story of Puerto Rican migration. Whether from the Midwest or South America, or local, each guy had some kind of idea about what it means to be Puerto Rican, and it seemed to be ALL negative. You may ask if I baited them with profile pics of me waving a Puerto Rican flag in my profile pictures, but no. I did not. Each one of them brought up identity first, and without shame, they expressed their negative reactions and stereotypes toward Puerto Ricans. Is it because so many Puerto Ricans moved to Orlando after Hurricane Maria? Hmmm. Maybe. But my feeling is that Maria just stirred up the bullshit that has always been a fact of life for all Puerto Ricans on the mainland, whether they arrived in the 1940s, 1980s or after the hurricane.

Thirty years ago, long before Maria, is when my family first arrived to Orlando from New York. At that time, there were a handful of Puerto Ricans here. The Riveras lived down the street. The Rios’s lived in the neighboring subdivision. But for the most part, East Orlando, about 20 miles from Disney World and the tourist attractions, was mostly gringo, and my middle school reflected those demographics.

Once I got to Winter Park High School (WPHS), established in 1923, there was a clear hierarchy of privilege. The school had such an esteemed reputation, wealthy families yanked their kids from private schools to attend this highly ranked public school. In 2008, Winter Park High School was listed at 160 in Newsweek’s 1,200 Top U.S. Schools, with the criteria being which schools have the largest percentage of students taking Honors Advanced Placement classes or International Baccalaureate exams. In 2011, The Washington Post’s annual ranking of American high schools identified WPHS as #156 in the country.

Puerto Rican kids like me in the early 1990s were lucky to be there. We were bused in from the outskirts. You would think I would be all paisan with the other Puerto Rican kids, but no. I learned to avoid the “Puerto Rican” hallway so I wouldn’t get harassed with air kisses and “Ay, Mami, ven-ca.” I learned to blend into my all-white AP calculus class and water polo team. I know. How bougie of me to take advanced placement classes and play a sport with the word “polo” in it. But I didn’t want to be associated with “the minority.”

Over the next 10-20 years, my aunts and uncles and cousins and their kids moved here, from the Bronx, New Jersey, Puerto Rico and South Florida. My parents were trendsetters, apparently. In 2018, my high school is now 43% “minority,” of which the majority is Hispanic, according to PublicSchoolReview.com. But check this out – 43% is low in comparison to the rest of Florida, where average “minority” enrollment is at 61%. This word “minority” no longer applies, eh? Time to update our language, perhaps to Spanish, along with all the new gender pronouns.

In other words, homeboy who just moved here two years ago from Wisconsin, who stereotyped me as “trouble,” is the minority. And little Colombian international student at the University of Central Florida who calls Puerto Ricans “cafre,” ie, low class, kind of deserves a Tinder-slap in the face. But hey, that would only prove his point, AND I’m the one who avoided the “Puerto Rican” hallways when I was in high school, so who am I to talk?

This is where Ricanstruction comes in. It’s not just a process of rebuilding the island after Hurricane Maria. It’s a process of reconstructing our identity, whether we live on the island or the mainland. A recent study of Floridians of Puerto Rican descent found we experienced “secondary trauma” from the storm, but also a renewed sense of identity and purpose.

“Mainland Puerto Ricans felt strengthened by the support they provided and received and by the belief that Puerto Ricans are resilient and strong-minded,” the report states. “For them, the storm strengthened their cultural pride and made them more determined to help and serve the island.

From personal experience, this study resonates with me – it’s what made me go to Puerto Rico last year to do relief work for a week and interview local nonprofits that were distributing gravity lights to people who still didn’t have power. A more prominent, public expression of this sentiment is Lin Manuel Miranda’s effort to bring his smash Broadway hit, “Hamilton” to the island this past January. Like me, Lin Manuel Miranda’s parents are from the island, and he felt the call to do something positive with his education and talent. He is also aware that his blood line back to Puerto Rico IS his identity. In addition to bringing joy to the people at $10 per ticket, he raised money for his Flamboyan Arts Fund by selling overpriced tickets for $5,000, $4,593 of which supports the arts community in Puerto Rico.

Similarly, the Brooklyn-based comic book artist who created “La Borinqueña,” which Kwest On reviewed last year, has announced a grants program looking for non-profit organizations based in Puerto Rico that are working in the areas that provide services to 1) children 2) women 3) arts and culture 4) wildlife and environmental protection 5) sustainable farming.

Meanwhile, the Orlandoricans have also been organizing and hosting cultural events that bring the island and mainland together. On the year anniversary of the hurricane, Iglesia Episcopal Jesus de Nazaret held a vigil to remember the 2,975 Puerto Ricans who died in the aftermath. According to Orlando Weekly, the event featured speeches from U.S Sen. Bill Nelson, Rep. Darren Soto, other elected officials and survivors, and a performance of bomba, a musical style and dance created centuries ago as a form of resistance by enslaved Africans who worked on the island’s plantations. For a Super Gringa like me, who grew up in Orlando rejecting anything that is Puerto Rican, I am amazed, proud and excited at this celebration of my culture while gearing up for the 2020 election.

According to Pew Research, Puerto Ricans account for a rapidly increasing share of Florida’s Hispanic eligible voters – U.S. citizens who are 18 years or older, regardless of whether they have registered to vote. Puerto Ricans now make up about a third (31%) of these adults, a similar share to that of Cubans (31%), according to a separate Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data.

Vamos4PR Action, a project of the Center for Popular Democracy, is actively registering Puerto Rican voters and currently looking to hire a Puerto Rican civic engagement coordinator specifically for Central Florida.

Hooray for the Orlandoricans for transforming their identity through these cultural and political events to the point Orlando’s mainstream institutions are following suit: The Orlando Ballet just announced it is donating 1,000 tickets to Puerto Ricans displaced by the hurricane. The annual University of Central Florida Celebrates the Arts festival coming up in April will feature works by Puerto Rican artists dealing with effect of Hurricane Maria on Puerto Rico.

We are no longer a “minority” hallway or neighborhood or island to be ignored, thanks to this Ricanstruction of our culture and identity. Perhaps now, the Tinder guys will stop calling us “cafre” or “trouble.” And instead, they will call us “inspiring.”